ASSYRIA

AND

BABYLONIA

In

both

Assyrian

and

Babylonian

history

there

are

still

wide

gaps,

but

exploration

is

continually

filling

them

up.

The

German

explorations

at

Asshur

added

quite

20

new

names

to

the

list

of

Assyrian

rulers.

It

is

dangerous

to

argue

that,

because

we

do

not

know

all

the

rulers

in

a

certain

period,

it

ought

to

be

reduced

in

length.

It

is

as

yet

impossible

to

reconcile

all

the

data,

because

we

are

not

sure

of

the

Icings

referred

to.

We

already

know

five

or

six

of

the

same

name,

and

it

may

well

be

that

we

mistake

the

reference.

(i)

Synchronous

History.

—

The

so-called

Synchronous

History

of

Assyria

and

Babylonia

dealt

with

the

wars

and

rectification

of

boundaries

between

the

two

countries

from

B.C.

1400

to

B.C.

1150

and

B.C.

900

to

B.C.

800;

and

the

Babylonian

Chronicle

gave

the

names

and

lengths

of

reign

of

the

kings

of

Assyria,

Babylonia,

and

Elam

from

B.C.

744

to

B.C.

668.

These

establish

a

number

of

synchronisms,

besides

making

considerable

contribu-tions

to

the

history.

The

bulk

of

the

history

is

derived

from

the

inscriptions

of

the

kings

themselves.

Here

there

is

an

often

remarked

difference

between

Assyrian

and

Babylonian

usage.

The

former

are

usually

very

full

concerning

the

wars

of

conquest,

the

latter

almost

entirely

concerned

with

temple

buildings

or

domestic

affairs,

such

as

palaces,

walls,

canals,

etc.

Many

Assyrian

kings

arrange

their

campaigns

in

chronological

order,

forming

what

are

called

Annals.

Others

are

content

to

sum

up

their

con-quests

in

a

list

of

lands

subdued.

We

rarely

have

any-thing

like

Annals

from

Babylonia.

The

value

to

be

attached

to

these

inscriptions

is

very

various.

They

are

contemporary,

and

for

geography

Invaluable.

A

king

would

hardly

boast

of

conquering

a

country

which

did

not

exist.

The

historical

value

is

ASSYRIA

AND

BABYLONIA

more

open

to

question.

A

'

conquest

'

meant

little

more

than

a

raid

successful

in

exacting

tribute.

The

Assyrians,

however,

gradually

learnt

to

consolidate

their

conquests.

They

planted

colonies

of

Assyrian

people;

endowing

them

with

conquered

lands.

They

transported

the

people

of

a

conquered

State

to

some

other

part

of

the

Empire,

allotting

them

lands

and

houses,

vineyards

and

gardens,

even

cattle,

and

so

endeavoured

to

destroy

national

spirit

and

produce

a

blended

population

of

one

language

and

one

civilization.

The

weakness

of

the

plan

lay

in

the

heavy

taxation

which

prevented

loyal

attachment.

The

population

of

the

Empire

had

no

objection

to

the

substitution

of

one

master

for

another.

The

demands

on

the

subject

States

for

men

and

supplies

for

the

incessant

wars

weakened

all

without

attaching

any.

The

population

of

Assyria

proper

was

insufficient

to

officer

and

garrison

so

large

an

empire,

and

every

change

of

monarch

was

the

signal

for

rebellion

in

all

outlying

parts.

A

new

dynasty

usually

had

to

recon-quer

most

of

the

Empire.

Civil

war

occurred

several

times,

and

always

led

to

great

weakness,

finally

rendering

the

Empire

an

easy

prey

to

the

invader.

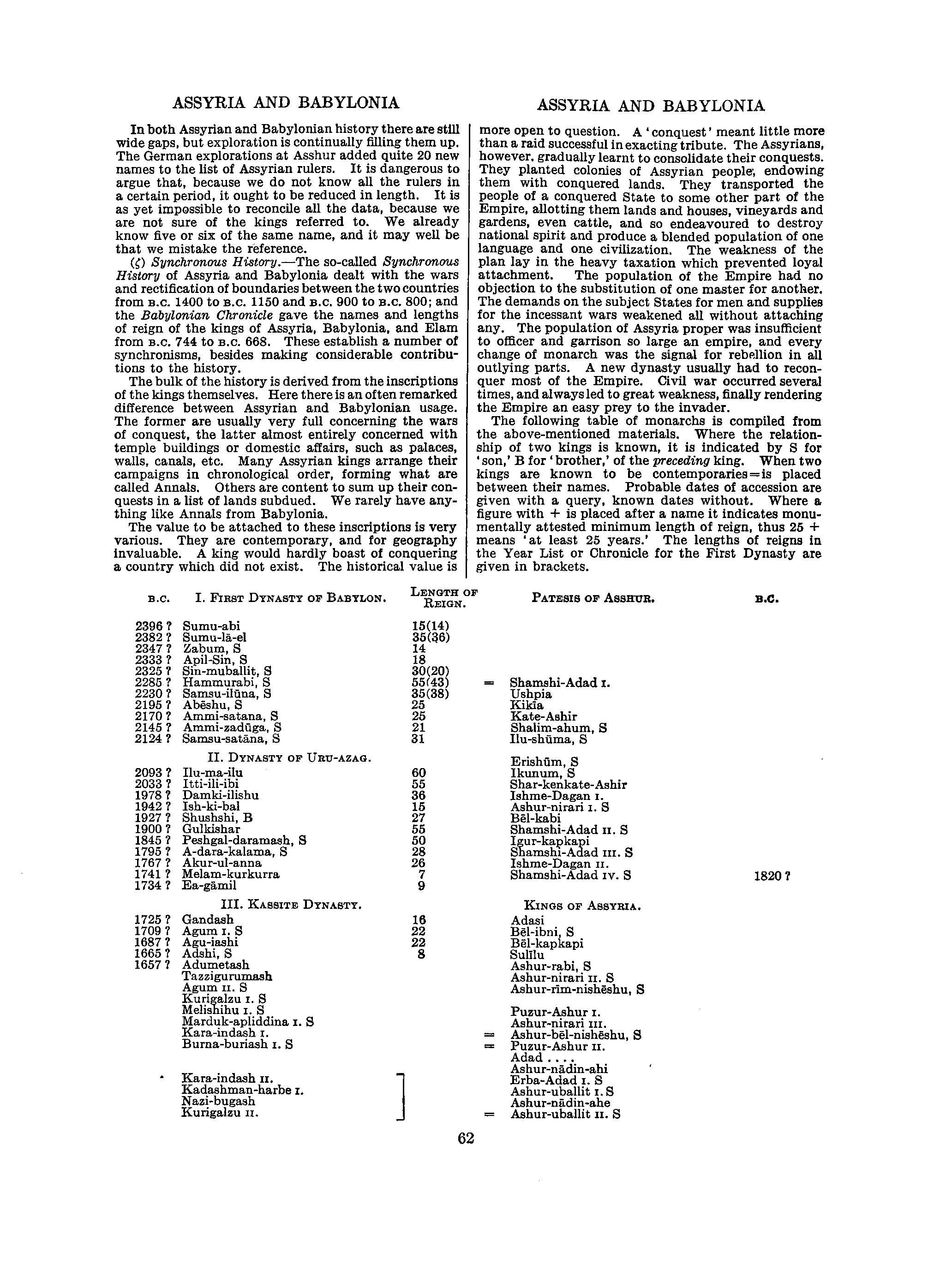

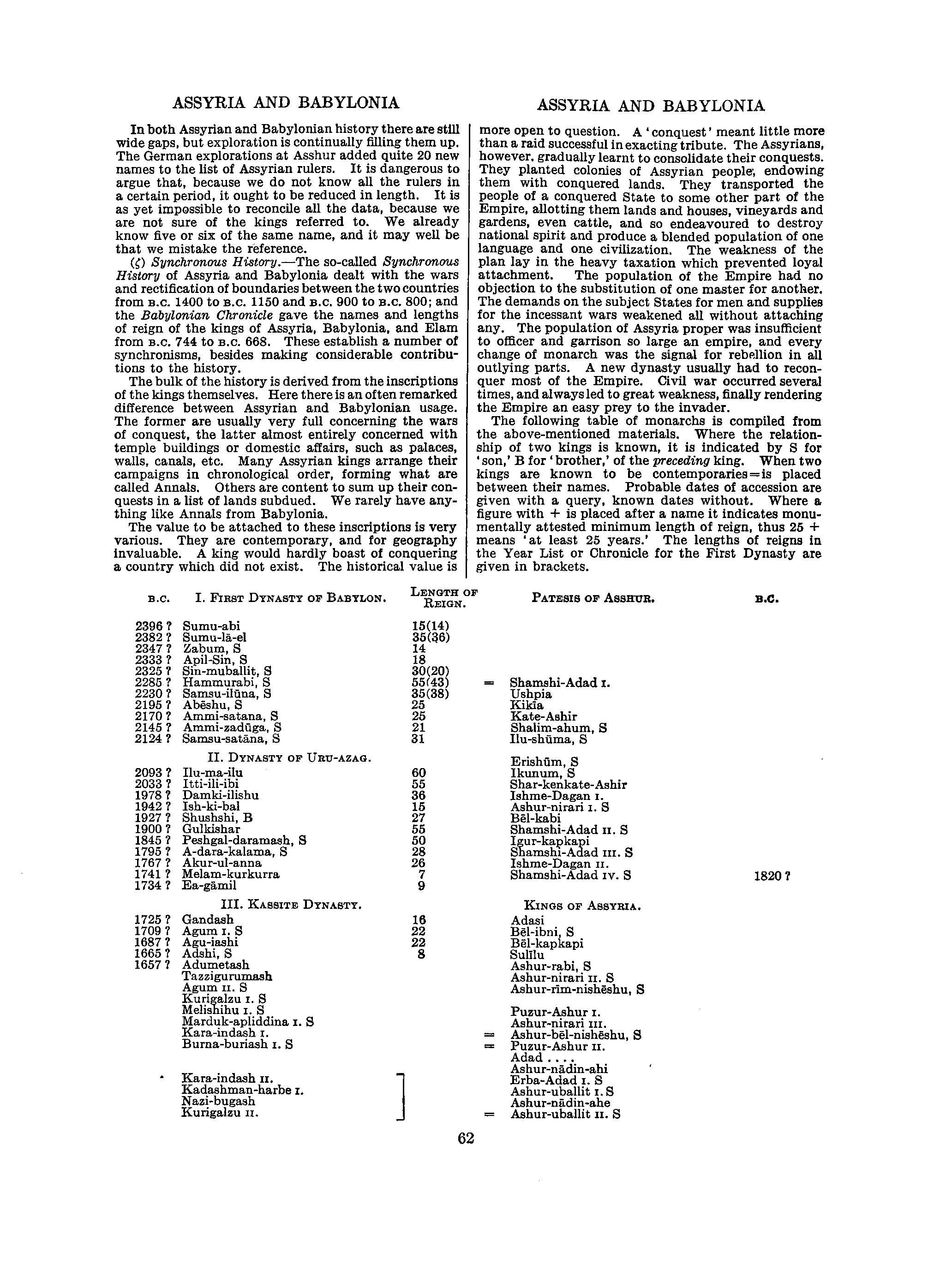

The

following

table

of

monarchs

is

compiled

from

the

above-mentioned

materials.

Where

the

relation-ship

of

two

kings

is

known,

it

is

indicated

by

S

for

'

son,'

B

for

'

brother,'

of

the

preceding

king.

When

two

kings

are

known

to

be

contemporaries

=

is

placed

between

their

names.

Probable

dates

of

accession

are

given

with

a

query,

known

dates

without.

Where

a

figure

with

+

is

placed

after

a

name

it

indicates

monu-mentally

attested

minimum

length

of

reign,

thus

25

+

means

'at

least

25

years.'

The

lengths

of

reigns

in

the

Year

List

or

Chronicle

for

the

First

Dynasty

are

given

in

brackets.