JEWELS

AND

PRECIOUS

STONES

the

Bible

besides

those

mentioned

above.

In

endeavour-ing

to

identify

the

stones

in

List

A,

three

things

have

to

be

liept

in

view.

From

the

dimensions

of

the

breast-plate

—

a

span

(8

or

9

inches)

each

way

(Ex

28")

—

the

12

stones

which

composed

it

must,

even

after

allowing

space

for

their

settings,

have

been

of

considerable

size,

and

therefore

of

only

moderate

rarity.

Further,

as

they

were

engraved

with

the

names

of

the

tribes,

they

can

have

been

of

only

moderate

hardness.

Lastly,

pref-erence

should

be

given

to

the

stones

which

archeeology

shows

to

have

been

actually

used

for

ornamental

work

in

early

Biblical

times.

In

regard

to

this

point,

the

article

by

Professor

Flinders

Petrie

(Hastings'

DB

iv.

619-21)

is

of

special

value.

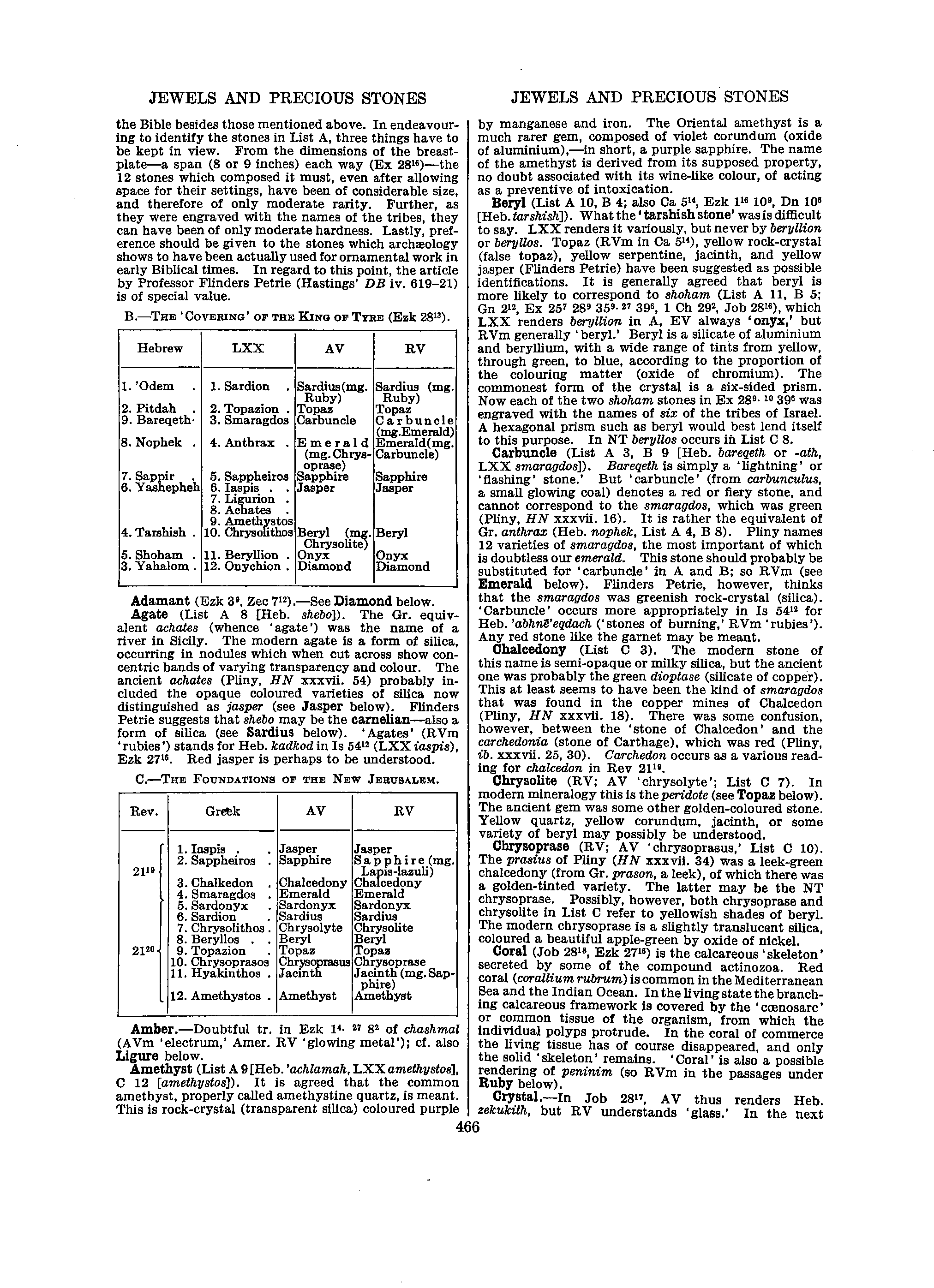

B.

—

The

'Covering'

or

the

Kino

of

Tyre

(Ezk

28^^),

Adamant

(Ezk

3',

Zee

7'^).

—

See

Diamond

below.

Agate

(List

A

8

[Heb.

shebd\).

The

Gr.

equiv-alent

achates

(whence

'agate')

was

the

name

of

a

river

in

Sicily.

The

modern

agate

is

a

form

of

silica,

occurring

in

nodules

which

when

out

across

show

con-centric

bands

of

varying

transparency

and

colour.

The

ancient

achates

(Pliny,

HN

xxxvii.

54)

probably

in-cluded

the

opaque

coloured

varieties

of

silica

now

distinguished

as

jasper

(see

Jasper

below).

Flinders

Petrie

suggests

that

shebo

may

be

the

camelian

—

also

a

form

of

sihca

(see

Sardius

below).

'Agates'

(RVm

'

rubies

')

stands

for

Heb.

kadkod

in

Is

5412

(LXX

iaspis),

Ezk

27".

Red

jasper

is

perhaps

to

be

understood.

Amber.

—

Doubtful

tr.

in

Ezk

!'■

"

8^

of

chashmal

(AVm

'electrum,'

Amer.

RV

'glowing

metal');

of.

also

Ligure

below.

Amethyst

(List

A

9

[Heb.

'achlamah,

LXX

amethystos],

C

12

[amethystos]).

It

is

agreed

that

the

common

amethyst,

properly

called

amethystine

quartz,

is

meant.

This

is

rock-crystal

(transparent

silica)

coloured

purple

JEWELS

AND

PRECIOUS

STONES

by

manganese

and

iron.

The

Oriental

amethyst

is

a

much

rarer

gem,

composed

of

violet

corundum

(oxide

of

aluminium),

—

in

short,

a

purple

sapphire.

The

name

of

the

amethyst

is

derived

from

its

supposed

property,

no

doubt

associated

with

its

wine-like

colour,

of

acting

as

a

preventive

of

intoxication.

Beryl

(List

A

10,

B

4;

also

Ca

5",

Ezk

1"

10',

Dn

10»

[Heb.

tarshish]).

What

the

'

tarshish

stone'

was

is

difficult

to

say.

LXX

renders

it

variously,

but

never

by

beryllion

or

beryllos.

Topaz

(RVm

in

Ca

5"),

yellow

rock-crystal

(false

topaz),

yellow

serpentine,

jacinth,

and

yellow

jasper

(Flinders

Petrie)

have

been

suggested

as

possible

identifications.

It

is

generally

agreed

that

beryl

is

more

likely

to

correspond

to

shoham

(List

A

11,

B

5;

Gn

212,

Ex

25'

28'

SS'-

"

39=,

1

Ch

29^

Job

28"),

which

LXX

renders

beryllion

in

A,

EV

always

'onyx,'

but

RVm

generally

'

beryl.'

Beryl

is

a

siUcate

of

aluminium

and

beryllium,

with

a

wide

range

of

tints

from

yellow,

through

green,

to

blue,

according

to

the

proportion

of

the

colouring

matter

(oxide

of

chromium).

The

commonest

form

of

the

crystal

is

a

six-sided

prism.

Now

each

of

the

two

shoham

stones

in

Ex

28»-

'°

39'

was

engraved

with

the

names

of

six

of

the

tribes

of

Israel.

A

hexagonal

prism

such

as

beryl

would

best

lend

itself

to

this

purpose.

In

NT

beryllos

occurs

in

List

C

8.

Carbuncle

(List

A

3,

B

9

[Heb.

bareqeth

or

-ath,

L.XX

smaragdos])

.

Bareqeth

is

simply

a,

'hghtning'

or

'flashing'

stone.'

But

'carbuncle'

(from

carlmnculus,

a

small

glowing

coal)

denotes

a

red

or

fiery

stone,

and

cannot

correspond

to

the

smaragdos,

which

was

green

(PUny,

HN

xxxvii.

16).

It

is

rather

the

equivalent

of

Gr.

anthrax

(Heb.

nophek.

List

A

4,

B

8).

PUny

names

12

varieties

of

smaragdos,

the

most

important

of

which

is

doubtless

our

emerald.

This

stone

should

probably

be

substituted

for

'carbuncle'

in

A

and

B;

so

RVm

(see

Emerald

below).

Flinders

Petrie,

however,

thinks

that

the

smaragdos

was

greenish

rock-crystal

(silica).

'Carbuncle'

occurs

more

appropriately

in

Is

6412

for

Heb.

'abhnS'egdach

('stones

of

burning,'

RVm

'rubies').

Any

red

stone

like

the

garnet

may

be

meant.

Chalcedony

(List

C

3).

The

modern

stone

of

this

name

is

semi-opaque

or

milky

silica,

but

the

ancient

one

was

probably

the

green

dioptase

(silicate

of

copper).

This

at

least

seems

to

have

been

the

kind

of

smaragdos

that

was

found

in

the

copper

mines

of

Chalcedon

(PUny,

HN

xxxvii.

18).

There

was

some

contusion,

however,

between

the

'stone

of

Chalcedon'

and

the

carchedonia

(stone

of

Carthage),

which

was

red

(PUny,

ib.

xxxvii.

25,

30).

Carchedon

occurs

as

a

various

read-ing

for

chalcedon

in

Eev

21".

Chrysolite

(RV;

AV

'chrysolyte';

List

C

7).

In

modern

mineralogy

this

is

the

peridote

(see

Topaz

below).

The

ancient

gem

was

some

other

golden-coloured

stone.

Yellow

quartz,

yellow

corundum,

jacinth,

or

some

variety

of

beryl

may

possibly

be

understood.

Chrysoprase

(RV;

AV

'chrysoprasus,'

List

C

10).

The

prasius

of

PUny

(HN

xxxvii.

34)

was

a

leek-green

chalcedony

(from

Gr.

prason,

a

leek),

of

which

there

was

a

golden-tinted

variety.

The

latter

may

be

the

NT

chrysoprase.

Possibly,

however,

both

chrysoprase

and

chrysoUte

in

List

C

refer

to

yeUowish

shades

of

beryl.

The

modern

chrysoprase

is

a

sUghtly

translucent

siUca,

coloured

a

beautiful

apple-green

by

oxide

of

nickel.

Coral

(Job

28",

Ezk

27'=)

is

the

calcareous

'skeleton'

secreted

by

some

of

the

compound

actinozoa.

Red

coral

(.corallium

rubrum)

is

common

in

the

Mediterranean

Sea

and

the

Indian

Ocean.

In

the

living

state

the

branch-ing

calcareous

framework

is

covered

by

the

'coenosarc'

or

common

tissue

of

the

organism,

from

which

the

individual

polyps

protrude.

In

the

coral

of

commerce

the

living

tissue

has

of

course

disappeared,

and

only

the

soUd

'skeleton'

remains.

'Coral'

is

also

a

possible

rendering

of

peninim

(so

RVm

in

the

passages

under

Ruby

below).

Crystal,—

In

Job

28",

AV

thus

renders

Heb.

zekukith,

but

RV

understands

'glass.'

In

the

next