MONEY

exact

weight

of

the

heavy

Babylonian

shekel

of

the

common

or

trade

standard.

For

the

weighing

of

silver,

on

the

other

hand,

this

shekel

was

discarded

for

practical

reasons.

Throughout

the

East

in

ancient

times

the

ratio

of

gold

to

silver

was

13J

:

1,

which

means

that

a

shekel

of

gold

could

buy

13i

times

the

same

weight

of

silver.

The

latest

explanation

of

this

invariable

ratio,

it

may

be

added

in

passing,

is

that

advocated

by

Wmckler

and

his

foUowera.

On

this,

the

so-called

'astral

mythology

theory

of

the

origin

of

Babylonian

culture,

gold,

the

yellow

metal,

was

specially

associated

with

the

sun,

while

the

paler

silver

was

the

special

'moon-metal.'

Accordingly

it

was

natural

to

fix

the

ratio

between

them

as

that

which

existed

between

the

year

and

the

month,

viz.

360

:

27

or

40

:

3.

In

ordinary

commerce,

however,

this

ratio

between

the

two

chief

media

of

exchange

was

extremely

incon-venient,

and

to

obviate

this

inconvenience,

the

weight

of

the

shekel

for

weighing

silver

was

altered

so

that

a

gold

shekel

might

be

exchanged

for

a

whole

number

of

silver

shekels.

This

alteration

was

effected

in

two

ways.

On

the

one

hand,

along

the

Babylonian

trade-routes

into

Asia

Minor

the

light

Babylonian

shekel

of

126

grains

was

raised

to

168

grains,

so

that

10

such

shekels

of

silver

now

represented

a

single

gold

shekel,

since

126X134

=

168X10.

On

the

other

hand,

the

great

commercial

cities

of

Phoenicia

introduced

a

silver

shekel

of

224

grains,

15

of

which

were

equivalent

to

one

heavy

Babylonian

gold

shekel

of

252

grains,

since

252

X

134=224X15.

This

224-grain

shekel

is

accordingly

known

as

the

Phoenician

standard.

It

was

on

this

standard

that

the

sacred

dues

of

the

Hebrews

were

calculated

(see

§

3);

on

it

also

the

famous

silver

shekels

and

half-shekels

were

struck

at

a

later

period

(§

5).

With

regard,

now,

to

the

intrinsic

value

of

the

above

gold

and

silver

shekels,

all

calculations

must

start

from

the

mint

price

of

gold,

which

in

Great

Britain

is

£3,

17s.

lOid.

per

ounce

of

480

grains.

This

gives

£2,

Is.

as

the

value

of

the

Hebrew

gold

shekel

of

252

gis.,

and

since

the

latter

was

the

equivalent

of

15

heavy

Phoe-nician

shekels,

2s.

9d.

represents

the

value

as

bullion

of

the

Hebrew

silver

shekel.

Of

course

the

purchasing

power

of

both

in

Bible

times,

which

is

the

real

test

of

the

value

of

money,

was

many

times

greater

than

their

equivalents

in

sterling

money

at

the

present

day.

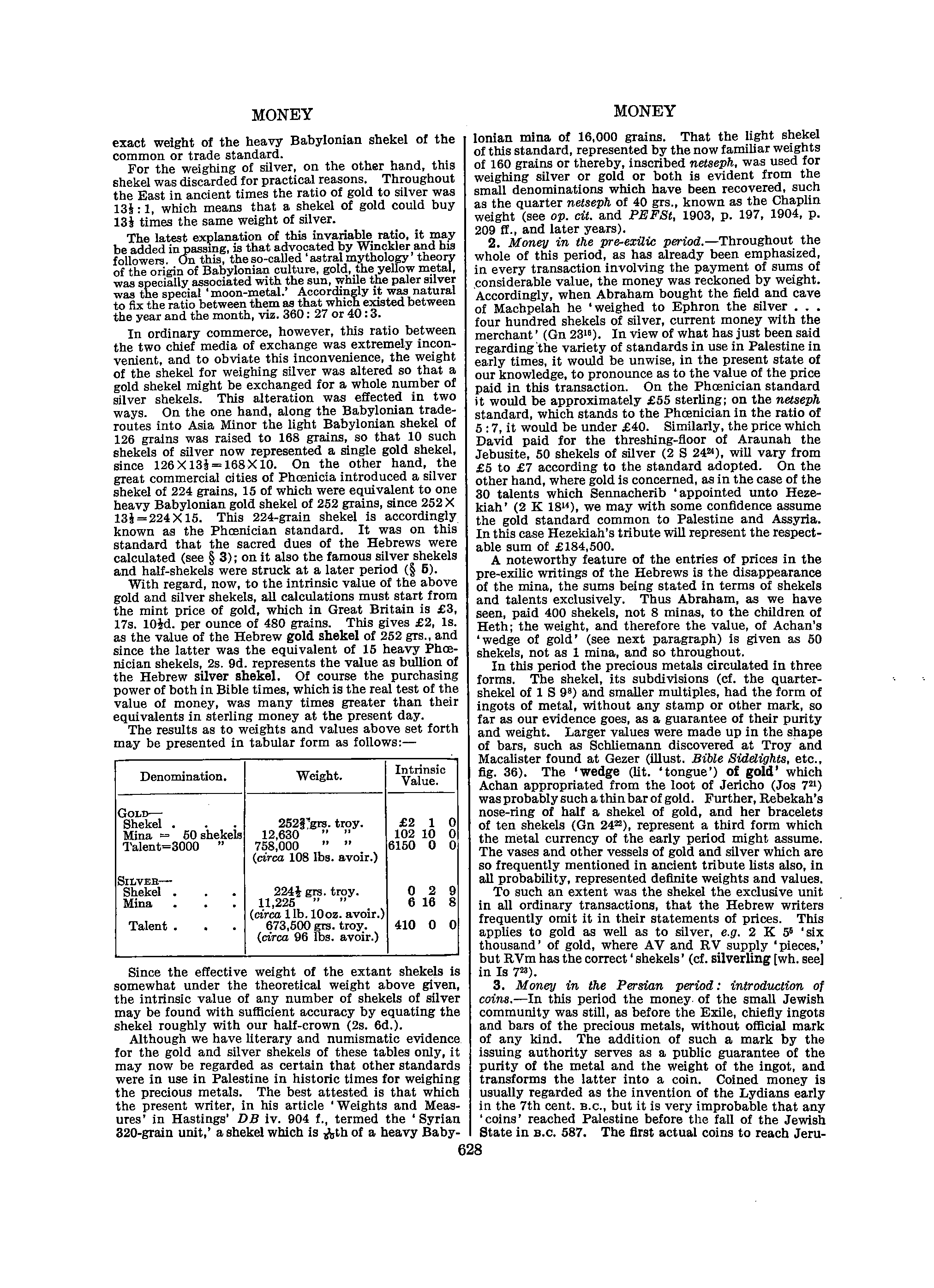

The

results

as

to

weights

and

values

above

set

forth

may

be

presented

in

tabular

form

as

follows:

—

Since

the

effective

weight

of

the

extant

shekels

is

somewhat

under

the

theoretical

weight

above

given,

the

intrinsic

value

of

any

number

of

shekels

of

silver

may

be

found

with

sufficient

accuracy

by

equating

the

shekel

roughly

with

our

half-crown

(2s.

6d.).

Although

we

have

literary

and

numismatic

evidence

for

the

gold

and

silver

shekels

of

these

tables

only,

it

may

now

be

regarded

as

certain

that

other

standards

were

in

use

in

Palestine

in

historic

times

for

weighing

the

precious

metals.

The

best

attested

is

that

which

the

present

writer,

in

his

article

'Weights

and

Meas-ures'

in

Hastings'

DB

iv.

904

f.,

termed

the

'

Syrian

320-grain

unit,'

a

shekel

which

is

A'h

o'

a

heavy

Baby-

MONEY

Ionian

mina

of

16,000

grains.

That

the

light

shekel

of

this

standard,

represented

by

the

now

familiar

weights

of

160

grains

or

thereby,

inscribed

netseph,

was

used

for

weighing

silver

or

gold

or

both

is

evident

from

the

small

denominations

which

have

been

recovered,

such

as

the

quarter

netseph

of

40

grs.,

known

as

the

Chaplin

weight

(see

op.

cit.

and

PEFSt,

1903,

p.

197,

1904,

p.

209

fl.,

and

later

years).

2.

Money

in

the

pre-exUic

period.

—

Throughout

the

whole

of

this

period,

as

has

already

been

emphasized,

in

every

transaction

involving

the

payment

of

sums

of

considerable

value,

the

money

was

reckoned

by

weight.

Accordingly,

when

Abraham

bought

the

field

and

cave

of

Machpelah

he

'weighed

to

Ephron

the

silver

.

.

.

four

hundred

shekels

of

silver,

current

money

with

the

merchant

'

(Gn

23").

In

view

of

what

has

just

been

said

regarding

the

variety

of

standards

in

use

in

Palestine

in

early

times,

it

would

be

unwise,

in

the

present

state

of

our

knowledge,

to

pronounce

as

to

the

value

of

the

price

paid

in

this

transaction.

On

the

Phoenician

standard

it

would

be

approximately

£55

sterling;

on

the

netseph

standard,

which

stands

to

the

Phoenician

in

the

ratio

of

6

:

7,

it

would

be

under

£40.

Similarly,

the

price

which

David

paid

for

the

threshing-floor

of

Araunah

the

Jebusite,

50

shekels

of

silver

(2

S

242»),

will

vary

from

£6

to

£7

according

to

the

standard

adopted.

On

the

other

hand,

where

gold

is

concerned,

as

in

the

case

of

the

30

talents

which

Sennacherib

'appointed

unto

Heze-kiah'

(2

K

18"),

we

may

with

some

confidence

assume

the

gold

standard

common

to

Palestine

and

Assyria.

In

this

case

Hezekiah's

tribute

will

represent

the

respect-able

sum

of

£184,500.

A

noteworthy

feature

of

the

entries

of

prices

in

the

pre-exilic

writings

of

the

Hebrews

is

the

disappearance

of

the

mina,

the

sums

being

stated

in

terms

of

shekels

and

talents

exclusively.

Thus

Abraham,

as

we

have

seen,

paid

400

shekels,

not

8

minas,

to

the

children

of

Heth;

the

weight,

and

therefore

the

value,

of

Achan's

'wedge

of

gold'

(see

next

paragraph)

is

given

as

50

shekels,

not

as

1

mina,

and

so

throughout.

In

this

period

the

precious

metals

circulated

in

three

forms.

The

shekel,

its

subdivisions

(cf.

the

quarter-

shekel

of

1

S

9«)

and

smaller

multiples,

had

the

form

of

ingots

of

metal,

without

any

stamp

or

other

mark,

so

far

as

our

evidence

goes,

as

a

guarantee

of

their

purity

and

weight.

Larger

values

were

made

up

in

the

shape

of

bars,

such

as

Schhemann

discovered

at

Troy

and

MacaUster

found

at

Gezer

(iUust.

Bible

Sidelights,

etc.,

fig.

36).

The

'wedge

(lit.

'tongue')

of

gold'

which

Achan

appropriated

from

the

loot

of

Jericho

(Jos

7")

was

probably

such

a

thin

bar

of

gold.

Further,

Rebekah's

nose-ring

of

half

a

shekel

of

gold,

and

her

bracelets

of

ten

shekels

(Gn

24^),

represent

a

third

form

which

the

metal

currency

of

the

early

period

might

assume.

The

vases

and

other

vessels

of

gold

and

silver

which

are

so

frequently

mentioned

in

ancient

tribute

hsts

also,

in

all

probability,

represented

definite

weights

and

values.

To

such

an

extent

was

the

shekel

the

exclusive

unit

in

all

ordinary

transactions,

that

the

Hebrew

writers

frequently

omit

it

in

their

statements

of

prices.

This

applies

to

gold

as

well

as

to

silver,

e.g.

2X5'

'six

thousand'

of

gold,

where

AV

and

RV

supply

'pieces,'

but

RVm

has

the

correct

'

shekels'

(cf.

silverling

[wh.

see]

in

Is

7^).

3.

Money

in

the

Persian

period:

introduction

of

coins.

—

In

this

period

the

money

of

the

small

Jewish

community

was

still,

as

before

the

Exile,

chiefly

ingots

and

bars

of

the

precious

metals,

without

official

mark

of

any

kind.

The

addition

of

such

a

mark

by

the

issuing

authority

serves

as

a

public

guarantee

of

the

purity

of

the

metal

and

the

weight

of

the

ingot,

and

transforms

the

latter

into

a

coin.

Coined

money

is

usually

regarded

as

the

invention

of

the

Lydians

early

in

the

7th

cent.

B.C.,

but

it

is

very

improbable

that

any

'coins'

reached

Palestine

before

the

fall

of

the

Jewish

State

in

B.C.

587.

The

first

actual

coins

to

reach

Jeru-