ISRAEL

longer

ascribe

to

him

either

the

Book

of

Proverbs

or

the

Book

of

Ecclesiastes,

his

reputation

for

wisdom

was

no

doubt

deserved.

Solomon's

reign

is

said

to

have

continued

forty

years

(1

K

11«).

If

this

be

so.

b.c.

977-937

is

probably

the

period

covered.

Towards

the

close

of

Solomon's

reign

the

tribe

of

Ephraim.

which

in

the

time

of

the

Judges

could

hardly

bear

to

allow

another

tribe

to

take

pre-cedence

of

it.

became

restless.

Its

leader

was

Jeroboam,

a

young

Ephraimlte

officer

to

whom

Solomon

had

entrusted

the

administration

of

the

affairs

of

the

Joseph

tribes

(1

K

H^s).

His

plans

for

rebelling

involved

the

fortifica-tion

of

his

native

city

Zeredah,

which

called

Solomon's

attention

to

his

plot,

and

he

fled

accordingly

to

Egypt,

where

he

found

refuge.

In

the

latter

country

the

21st

dynasty,

with

which

Solomonhad

intermarried,

had

passed

away,

and

the

Libyan

Shishak

(Sheshonk),

the

founder

of

the

22nd

dynasty,

had

ascended

the

throne

in

B.C.

945.

He

ruled

a

united

Egypt,

and

entertained

ambitions

to

renew

Egypt's

Asiatic

empire.

Shishak

accordingly

welcomed

Jeroboam

and

offered

him

asylum,

but

was

not

prepared

while

Solomon

lived

to

give

him

an

army

with

which

to

attack

his

master.

16.

Division

of

the

kingdom.

—

Upon

the

death

of

Solomon,

his

son

Rehoboam

seems

to

have

been

pro-claimed

king

in

Judah

without

opposition,

but

as

some

doubt

concerning

the

loyalty

of

the

other

tribes,

of

which

Ephraim

was

leader,

seems

to

have

existed,

Rehoboam

went

to

Shechem

to

be

anointed

as

king

at

their

ancient

shrine

(1

K

12i^).

Jeroboam,

having

been

informed

in

his

Egyptian

retreat

of

the

progress

of

affairs,

returned

to

Shechem

and

prompted

the

elders

of

the

tribes

assembled

there

to

exact

from

Rehoboam

a

promise

that

in

case

they

accepted

him

as

monarch

he

would

relieve

them

of

the

heavy

taxation

which

his

father

had

imposed

upon

them.

After

considering

the

matter

three

days,

Rehoboam

rejected

the

advice

of

the

older

and

wiser

counsellors,

and

gave

such

an

answer

as

one

bred

to

the

doctrine

of

the

Divine

right

of

kings

would

naturally

give.

The

substance

of

his

reply

was:

'

My

little

finger

shall

be

thicker

than

my

father's

loins.'

As

the

result

of

this

answer

all

the

tribes

except

Judah

and

a

portion

of

Benjamin

refused

to

acknowledge

the

descendant

of

David,

and

made

Jeroboam

their

king.

Judah

remained

faithful

to

the

heir

of

her

old

hero,

and,

because

Jerusalem

was

on

the

border

of

Benjamin,

the

Judeean

kings

were

able

to

retain

a

strip

of

the

land

of

that

tribe

varying

from

time

to

time

in

width

from

four

to

eight

miles.

All

else

was

lost

to

the

Davidic

dynasty.

The

chief

forces

which

produced

this

disruption

were

economic,

but

they

were

not

the

only

forces.

Religious

conservatism

also

did

its

share.

Solomon

had

in

many

ways

contravened

the

religious

customs

of

his

nation.

His

brazen

altar

and

brazen

utensils

for

the

Temple

were

not

orthodox.

Although

he

made

no

attempt

to

centralize

the

worship

at

his

Temple

(which

was

in

reality

his

royal

chapel),

his

disregard

of

sacred

ritual

had

its

effect,

and

Jeroboam

made

an

appeal

to

religious

conservatism

when

he

said,

'

Behold

thy

gods,

O

Israel,

which

brought

thee

up

out

of

the

land

of

Egypt.'

Since

we

know

the

history

only

through

the

work

of

a

propagandist

of

a

later

type

of

religion,

the

attitude

of

Jeroboam

has

long

been

misunderstood.

He

was

not

a

religious

innovator,

but

a

religious

con-servative.

When

the

kingdom

was

divided,

the

tributary

States

of

course

gained

their

independence,

and

Israel's

empire

was

at

an

end.

The

days

of

her

political

glory

had

been

less

than

a

century,

and

her

empire

passed

away

never

to

return.

The

nation,

divided

and

its

parts

often

warring

with

one

another,

could

not

easily

become

again

a

power

of

importance.

16.

From

Jeroboam

to

Ahab

(937-875).

—

After

the

division

of

the

kingdom,

the

southern

portion,

consisting

chiefly

of

the

tribe

of

Judah,

was

known

as

the

kingdom

ISRAEL

of

Judah,

while

the

northern

division

was

known

as

the

kingdom

of

Israel.

Judah

remained

loyal

to

the

Davidic

dynasty

as

long

as

she

maintained

her

in-dependence,

but

in

Israel

frequent

changes

of

dynasty

occurred.

Only

one

family

furnished

more

than

four

monarchs,

some

only

two,

while

several

failed

to

transmit

the

throne

at

all.

The

kings

during

the

first

period

were:

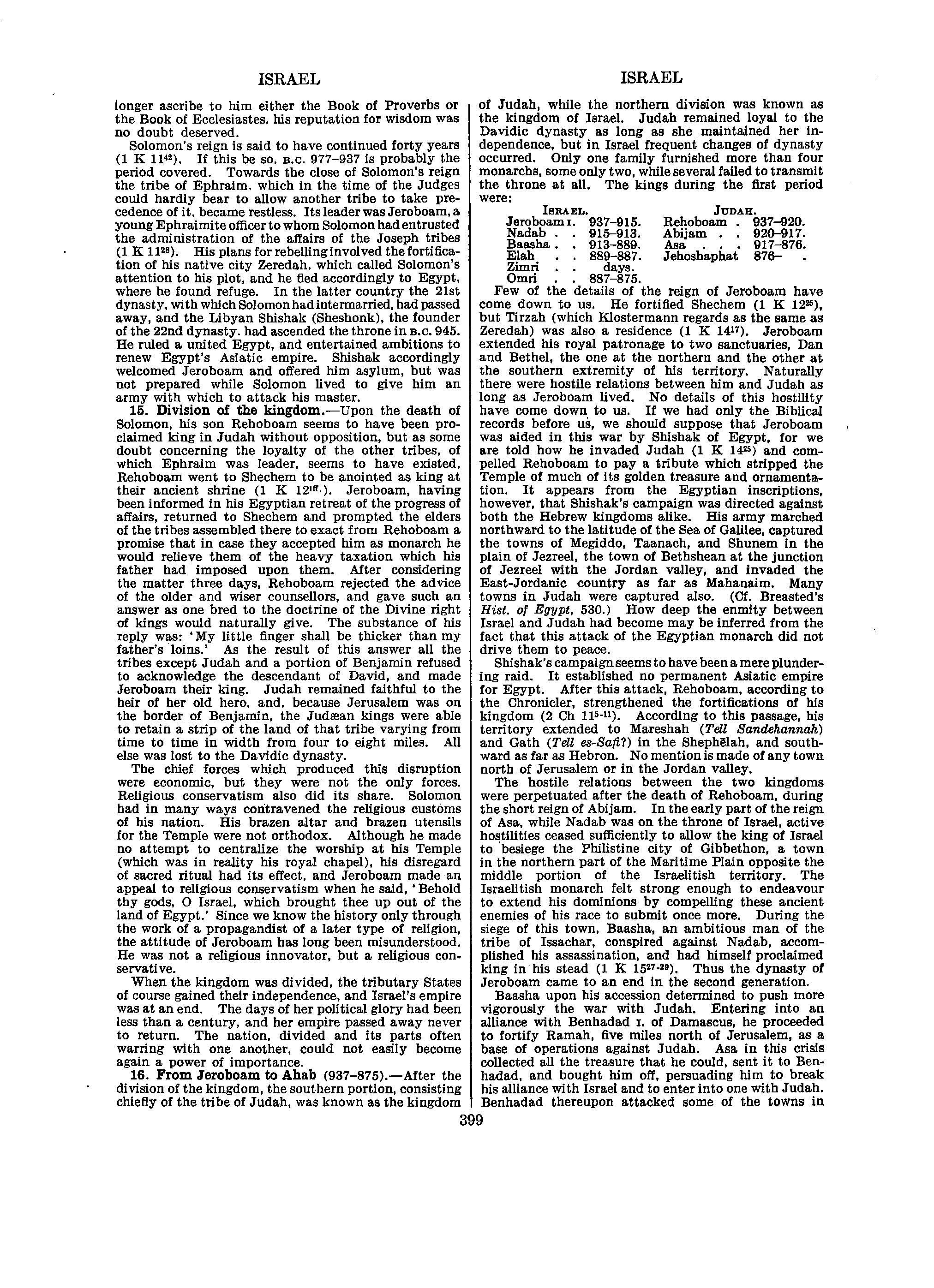

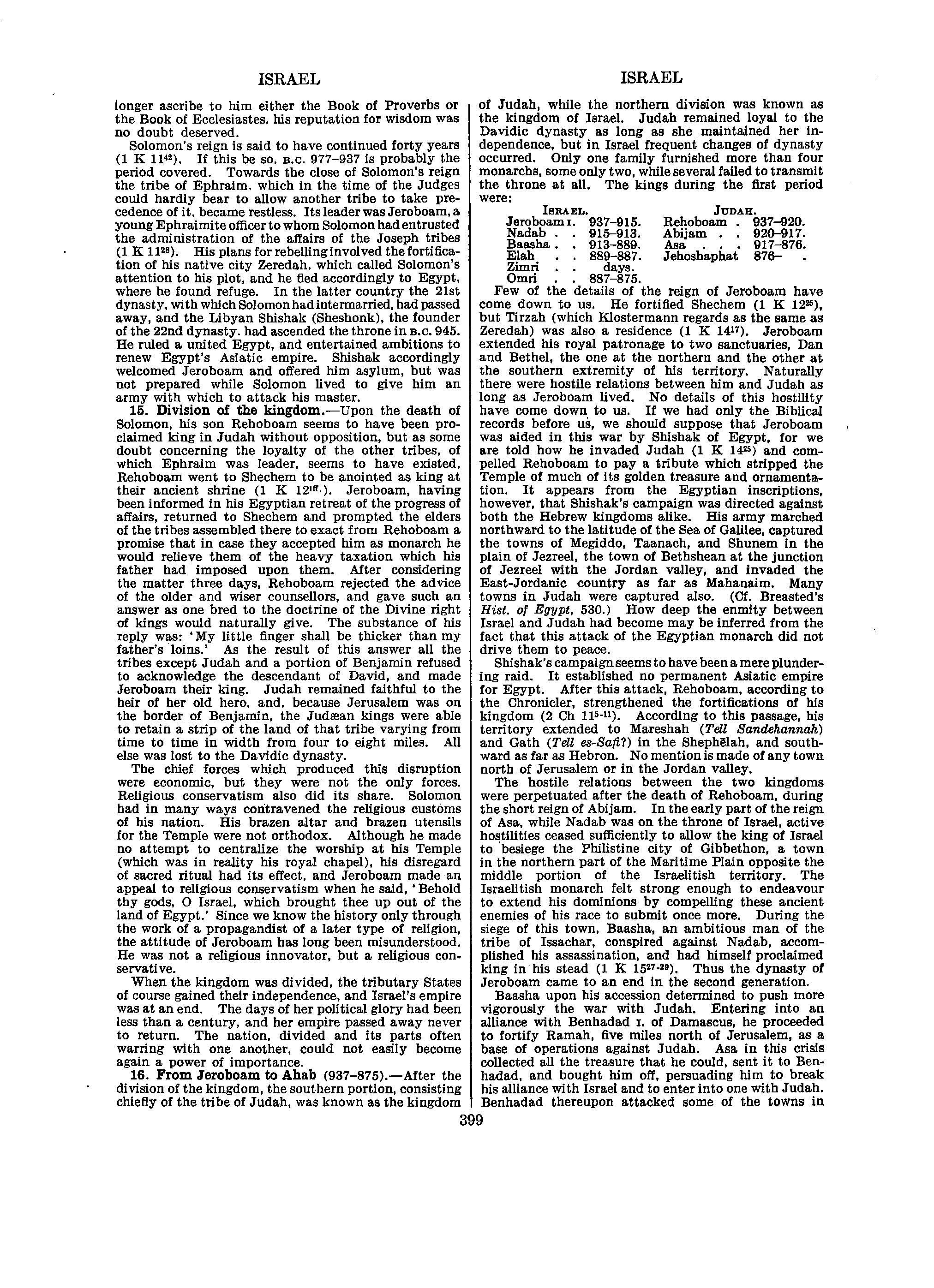

IbrA-el.

Judah.

Jeroboami.

937-915.

Rehoboam

.

937-920.

Nadab

.

.

915-913.

Abijam

.

.

920-917.

Baasha

.

.

913-889.

Asa

.

.

.

917-876.

Elah

.

.

889-887.

Jehoshaphat

876-

Zimri

.

.

days.

Omri

.

.

887-875.

Few

of

the

details

of

the

reign

of

Jeroboam

have

come

down

to

us.

He

fortified

Shechem

(1

K

12»),

but

Tirzah

(which

Klostermann

regards

as

the

same

as

Zeredah)

was

also

a

residence

(1

K

14").

Jeroboam

extended

his

royal

patronage

to

two

sanctuaries,

Dan

and

Bethel,

the

one

at

the

northern

and

the

other

at

the

southern

extremity

of

his

territory.

Naturally

there

were

hostile

relations

between

him

and

Judah

as

long

as

Jeroboam

lived.

No

details

of

this

hostility

have

come

down

to

us.

If

we

had

only

the

Biblical

records

before

us,

we

should

suppose

that

Jeroboam

was

aided

in

this

war

by

Shishak

of

Egypt,

for

we

are

told

how

he

invaded

Judah

(1

K

14»)

and

com-pelled

Rehoboam

to

pay

a

tribute

which

stripped

the

Temple

of

much

of

its

golden

treasure

and

ornamenta-tion.

It

appears

from

the

Egyptian

inscriptions,

however,

that

Shishak's

campaign

was

directed

against

both

the

Hebrew

kingdoms

alike.

His

army

marched

northward

to

the

latitude

of

the

Sea

of

Galilee,

captured

the

towns

of

Megiddo,

Taanach,

and

Shunem

in

the

plain

of

Jezreel,

the

town

of

Bethsheau

at

the

junction

of

Jezreel

with

the

Jordan

valley,

and

Invaded

the

East-Jordanic

country

as

far

as

Mahanaim.

Many

towns

in

Judah

were

captured

also.

(Cf.

Breasted's

Hist,

of

Egypt,

530.)

How

deep

the

enmity

between

Israel

and

Judah

had

become

may

be

inferred

from

the

fact

that

this

attack

of

the

Egyptian

monarch

did

not

drive

them

to

peace.

Shishak's

campaign

seems

to

have

been

a

mere

plunder-ing

raid.

It

established

no

permanent

Asiatic

empire

for

Egypt.

After

this

attack,

Rehoboam,

according

to

the

Chronicler,

strengthened

the

fortifications

of

his

kingdom

(2

Ch

ll^-u).

According

to

this

passage,

his

territory

extended

to

Mareshah

(Tell

Sandehannah)

and

Gath

(.Tell

es-Safl?)

in

the

Shephglah,

and

south-ward

as

far

as

Hebron.

No

mention

is

made

of

any

town

north

of

Jerusalem

or

in

the

Jordan

valley.

The

hostile

relations

between

the

two

kingdoms

were

perpetuated

after

the

death

of

Rehoboam,

during

the

short

reign

of

Abijam.

In

the

early

part

of

the

reign

of

Asa,

while

Nadab

was

on

the

throne

of

Israel,

active

hostilities

ceased

sufficiently

to

allow

the

king

of

Israel

to

besiege

the

Philistine

city

of

Gibbethon,

a

town

in

the

northern

part

of

the

Maritime

Plain

opposite

the

middle

portion

of

the

Israelitish

territory.

The

Israelitish

monarch

felt

strong

enough

to

endeavour

to

extend

his

dominions

by

compelUng

these

ancient

enemies

of

his

race

to

submit

once

more.

During

the

siege

of

this

town,

Baasha,

an

ambitious

man

of

the

tribe

of

Issachar,

conspired

against

Nadab,

accom-plished

his

assassination,

and

had

himself

proclaimed

king

in

his

stead

(1

K

15"-2»).

Thus

the

dynasty

of

Jeroboam

came

to

an

end

in

the

second

generation.

Baasha

upon

his

accession

determined

to

push

more

vigorously

the

war

with

Judah.

Entering

into

an

alliance

with

Benhadad

i.

of

Damascus,

he

proceeded

to

fortify

Ramah,

five

miles

north

of

Jerusalem,

as

a

base

of

operations

against

Judah.

Asa

in

this

crisis

collected

all

the

treasure

that

he

could,

sent

it

to

Ben-hadad,

and

bought

him

off,

persuading

him

to

break

his

alUance

with

Israel

and

to

enter

into

one

with

Judah.

Benhadad

thereupon

attacked

some

of

the

towns

in