ISRAEL

north-eastern

Galilee,

and

Baasha

was

compelled

to

desist

from

his

Judaean

campaign

and

defend

his

own

borders.

Asa

tools

this

opportunity

to

fortify

Geba,

about

eight

miles

north-east

of

Jerusalem,

and

Mizpeh,

five

miles

to

the

north-west

of

it

(1

K

IS's-z').

The

only

other

important

event

of

Asa's

reign

known

to

us

consisted

of

the

erection

by

Asa's

mother'of

an

asKirah

made

in

a

disgustingly

realistic

form,

which

so

shocked

the

sense

of

the

time

that

Asa

was

compelled

to

remove

it

(151=).

Of.,

for

fuller

discussion,

below,

II.

§

1

(3).

During

the

reign

of

Elah

an

attempt

was

made

once

more

to

capture

Gibbethon.

The

siege

was

being

prosecuted

by

an

able

general

named

Omri,

while

the

weak

king

was

enjoying

himself

at

Tirzah,

which

had

been

the

royal

residence

since

the

days

of

Jeroboam.

While

the

king

was

in

a

drunken

brawl

he

was

killed

by

Zimri,

the

commander

of

his

chariots,

who

was

then

himself

proclaimed

king.

Omri,

however,

upon

hearing

of

this,

hastened

from

Gibbethon

to

Tirzah,

overthrew

and

slew

Zimri,

and

himself

became

king.

Thus

once

more

did

the

dynasty

change.

Omri

proved

one

of

the

ablest

rulers

the

Northern

Kingdom

ever

had.

The

Bible

tells

us

little

of

him,

but

the

information

we

derive

from

outside

sources

enables

us

to

place

him

in

proper

perspective.

His

fame

spread

to

Assyria,

where,

even

after

his

dynasty

had

been

overthrown,

he

was

thought

to

be

the

ancestor

of

Israelitish

kings

(cf.

KIB

i.

151).

Omri,

perceiving

the

splendid

military

possibilities

of

the

hill

of

Samaria,

chose

that

for

his

capital,

fortified

it,

and

made

it

one

of

his

residences,

thus

introducing

to

history

a

name

destined

in

succeeding

generations

to

play

an

important

part.

He

appears

to

have

made

a

peaceful

alliance

with

Damascus,

so

that

war

between

the

two

kingdoms

ceased.

He

also

formed

an

alliance

with

the

king

of

Tyre,

taking

Jezebel,

the

daughter

of

the

Tynan

king

Ethbaal,

as

a

wife

for

his

son

Ahab.

We

also

learn

from

the

Moabite

Stone

that

Omri

con-quered

Moab,

compelling

the

Moabites

to

pay

tribute.

According

to

the

Bible,

this

tribute

was

paid

in

wool

(2

K

3«).

Scanty

as

our

information

is,

it

furnishes

evidence

that

both

in

military

and

in

civil

aflairs

Omri

must

be

counted

as

the

ablest

ruler

of

the

Northern

Kingdom.

Of

the

nature

of

the

relations

between

Israel

and

Judah

during

his

reign

we

have

no

hint.

Probably,

however,

peace

prevailed,

since

we

find

the

next

two

kings

of

these

kingdoms

in

alUance.

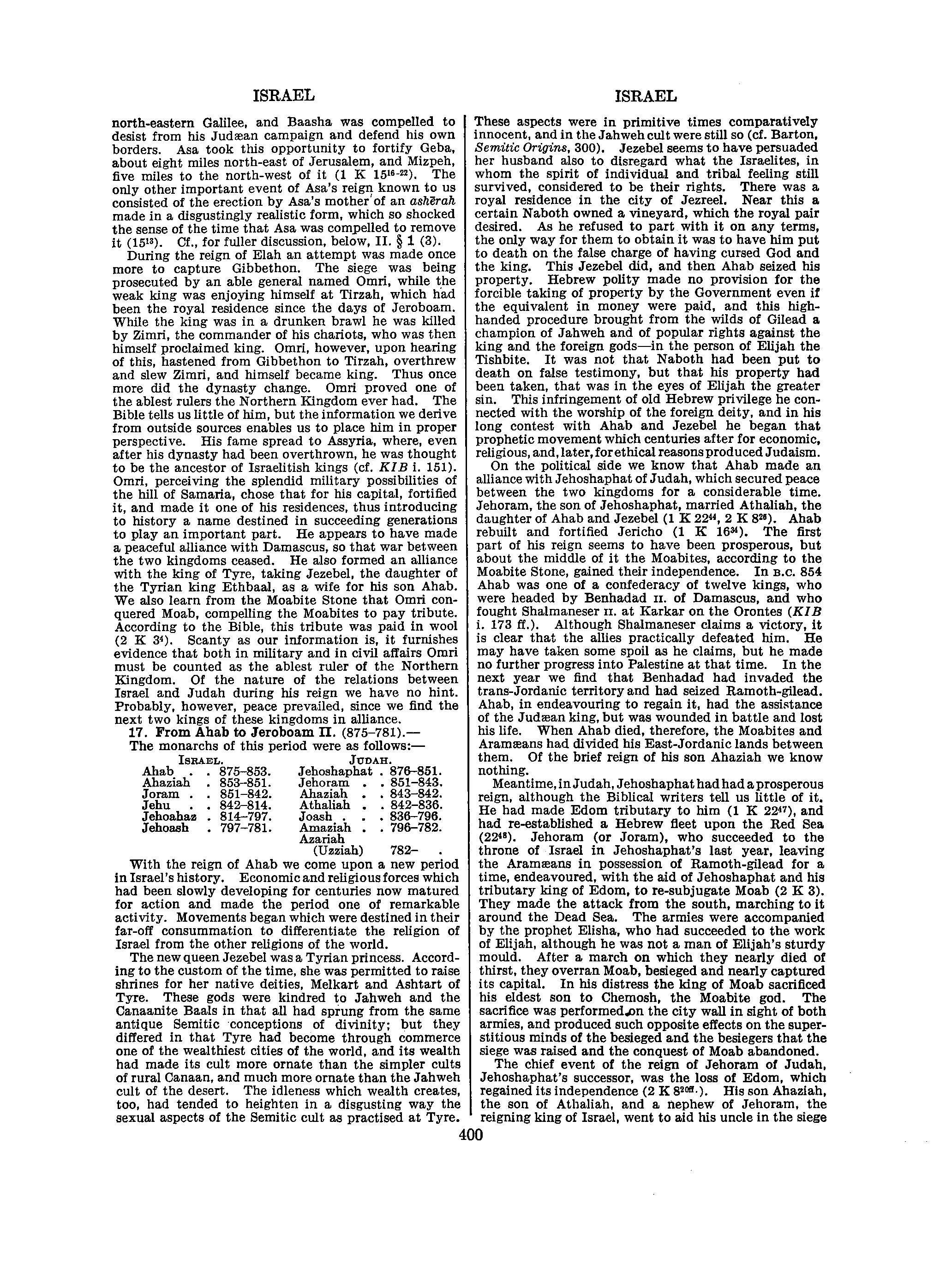

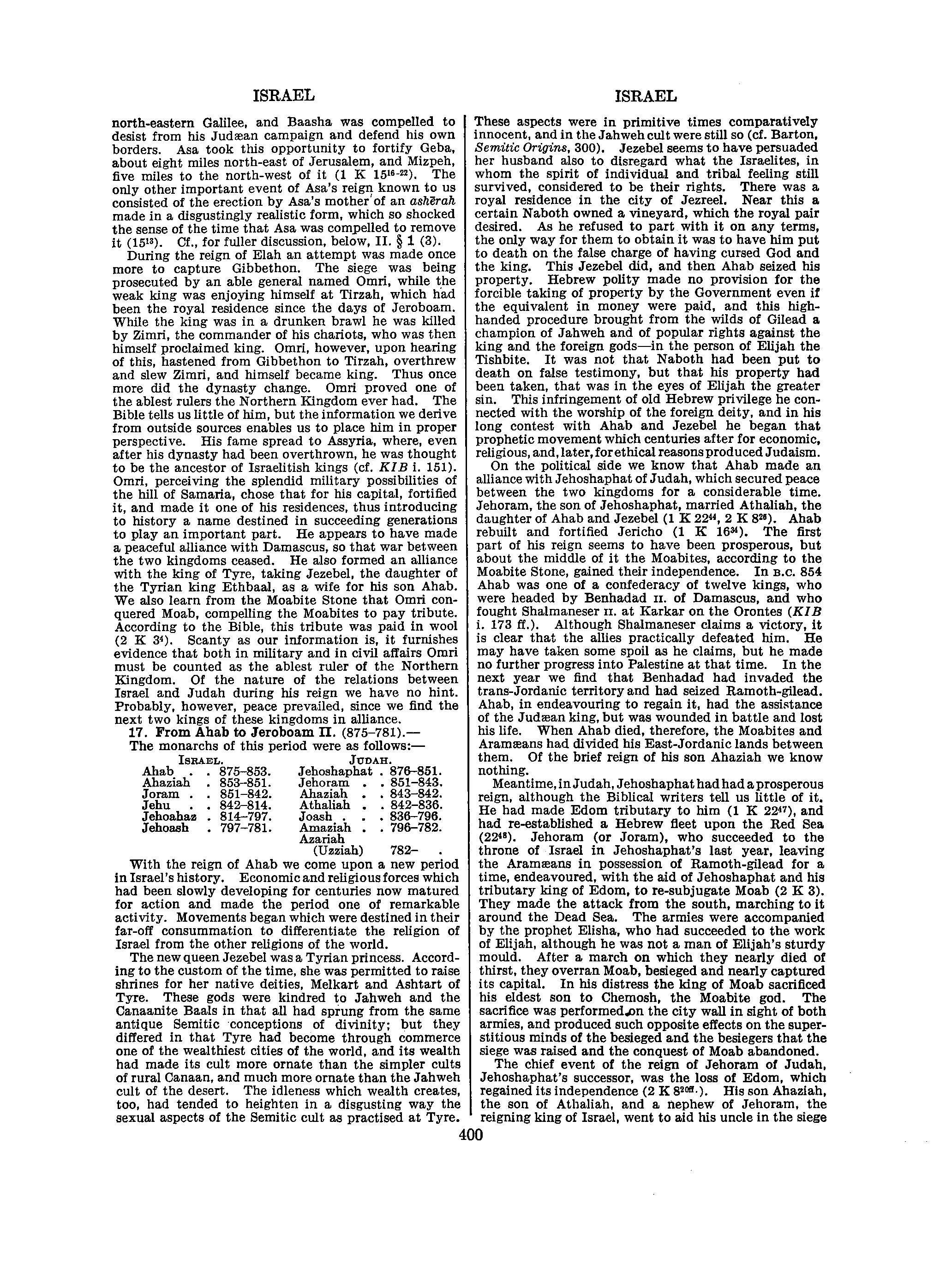

17.

From

Ahab

to

Jeroboam

11.

(875-781).

—

The

monarchs

of

this

period

were

as

follows:

—

Israel.

Jddah.

Ahab

.

.

875-853.

Jehoshaphat

.

876-851.

Ahaziah

.

853-851.

Jehoram

.

.

851-843.

Joram

.

.

851-842.

Ahaziah

.

.

843-842.

Jehu

.

.

842-814.

Athaliah

.

.

842-836.

Jehoahaz

.

814-797.

Joash

.

.

.

836-796.

Jehoash

.

797-781.

Amaziah

.

.

796-782.

Azanah

(Uzziah)

782-

.

With

the

reign

of

Ahab

we

come

upon

a

new

period

in

Israel's

history.

Economic

and

reUgious

forces

which

had

been

slowly

developing

for

centuries

now

matured

for

action

and

made

the

period

one

of

remarkable

activity.

Movements

began

which

were

destined

in

their

far-off

consummation

to

differentiate

the

reUgion

of

Israel

from

the

other

religions

of

the

world.

The

new

queen

Jezebel

was

a

Tyrian

princess.

Accord-ing

to

the

custom

of

the

time,

she

was

permitted

to

raise

shrines

for

her

native

deities,

Melkart

and

Ashtart

of

Tyre.

These

gods

were

kindred

to

Jahweh

and

the

Canaanite

Baals

in

that

all

had

sprung

from

the

same

antique

Semitic

conceptions

of

divinity;

but

they

differed

in

that

Tyre

had

become

through

commerce

one

of

the

wealthiest

cities

of

the

world,

and

its

wealth

had

made

its

cult

more

ornate

than

the

simpler

cults

of

rural

Canaan,

and

much

more

ornate

than

the

Jahweh

cult

of

the

desert.

The

idleness

which

wealth

creates,

too,

had

tended

to

heighten

in

a

disgusting

way

the

sexual

aspects

of

the

Semitic

cult

as

practised

at

Tyre.

ISRAEL

These

aspects

were

in

primitive

times

comparatively

innocent,

and

in

the

Jahweh

cult

were

still

so

(cf

.

Barton,

Semitic

Origins,

300).

Jezebel

seems

to

have

persuaded

her

husband

also

to

disregard

what

the

Israelites,

in

whom

the

spirit

of

Individual

and

tribal

feeling

still

survived,

considered

to

be

their

rights.

There

was

a

royal

residence

in

the

city

of

Jezreel.

Near

this

a

certain

Naboth

owned

a

vineyard,

which

the

royal

pair

desired.

As

he

refused

to

part

with

it

on

any

terms,

the

only

way

for

them

to

obtain

it

was

to

have

him

put

to

death

on

the

false

charge

of

having

cursed

God

and

the

king.

This

Jezebel

did,

and

then

Ahab

seized

his

property.

Hebrew

polity

made

no

provision

for

the

forcible

taking

of

property

by

the

Government

even

if

the

equivalent

in

money

were

paid,

and

this

high-handed

procedure

brought

from

the

wilds

of

Gilead

a

champion

of

Jahweh

and

of

popular

rights

against

the

king

and

the

foreign

gods

—

^in

the

person

of

Elijah

the

Tishbite.

It

was

not

that

Naboth

had

been

put

to

death

on

false

testimony,

but

that

his

property

had

been

taken,

that

was

in

the

eyes

of

Elijah

the

greater

sin.

This

infringement

of

old

Hebrew

privilege

he

con-nected

with

the

worship

of

the

foreign

deity,

and

in

his

long

contest

with

Ahab

and

Jezebel

he

began

that

prophetic

movement

which

centuries

after

for

economic,

religious,

and,

later.forethicalreasonsproduced

Judaism.

On

the

political

side

we

know

that

Ahab

made

an

alliance

with

Jehoshaphat

of

Judah,

which

secured

peace

between

the

two

kingdoms

for

a

considerable

time.

Jehoram,

the

son

of

Jehoshaphat,

married

Athaliah,

the

daughter

of

Ahab

and

Jezebel

(1

K

22«,

2

K

8^').

Ahab

rebuilt

and

fortified

Jericho

(1

K

16M).

The

first

part

of

his

reign

seems

to

have

been

prosperous,

but

about

the

middle

of

it

the

Moabites,

according

to

the

Moabite

Stone,

gained

their

independence.

In

B.C.

854

Ahab

was

one

of

a

confederacy

of

twelve

kings,

who

were

headed

by

Benhadad

11.

of

Damascus,

and

who

fought

Shalmaneser

11.

at

Karkar

on

the

Orontes

(KIB

i.

173

fl.).

Although

Shalmaneser

claims

a

victory,

it

is

clear

that

the

allies

practically

defeated

him.

He

may

have

taken

some

spoil

as

he

claims,

but

he

made

no

further

progress

into

Palestine

at

that

time.

In

the

next

year

we

find

that

Benhadad

had

invaded

the

trans-

Jordanic

territory

and

had

seized

Ramoth-gilead.

Ahab,

in

endeavouring

to

regain

it,

had

the

assi.stance

of

the

Judaean

king,

but

was

wounded

in

battle

and

lost

his

Ufe.

When

Ahab

died,

therefore,

the

Moabites

and

Aramseans

had

divided

his

East-Jordanic

lands

between

them.

Of

the

brief

reign

of

his

son

Ahaziah

we

know

nothing.

Meantime,

in

Judah,

Jehoshaphat

had

had

a

prosperous

reign,

although

the

BibUcal

writers

tell

us

little

of

it.

He

had

made

Edom

tributary

to

him

(1

K

22^'),

and

had

re-established

a

Hebrew

fleet

upon

the

Bed

Sea

(22").

Jehoram

(or

Joram),

who

succeeded

to

the

throne

of

Israel

In

Jehoshaphat's

last

year,

leaving

the

Aramjeans

in

possession

of

Ramoth-gilead

for

a

time,

endeavoured,

with

the

aid

of

Jehoshaphat

and

his

tributary

king

of

Edom,

to

re-subjugate

Moab

(2

K

3).

They

made

the

attack

from

the

south,

marching

to

it

around

the

Dead

Sea.

The

armies

were

accompanied

by

the

prophet

Elisha,

who

had

succeeded

to

the

work

of

Elijah,

although

he

was

not

a

man

of

Elijah's

sturdy

mould.

After

a

march

on

which

they

nearly

died

of

thirst,

they

overran

Moab,

besieged

and

nearly

captured

its

capital.

In

his

distress

the

king

of

Moab

sacrificed

his

eldest

son

to

Chemosh,

the

Moabite

god.

The

sacrifice

was

performed^n

the

city

wall

in

sight

of

both

armies,

and

produced

such

opposite

effects

on

the

super-stitious

minds

of

the

besieged

and

the

besiegers

that

the

siege

was

raised

and

the

conquest

of

Moab

abandoned.

The

chief

event

of

the

reign

of

Jehoram

of

Judah,

Jehoshaphat's

successor,

was

the

loss

of

Edom,

which

regained

its

independence

(2

K

S'"").

His

son

Ahaziah,

the

son

of

Athaliah,

and

a

nephew

of

Jehoram,

the

reigning

king

of

Israel,

went

to

aid

his

uncle

in

the

siege