PLAGUES

OF

EGYPT

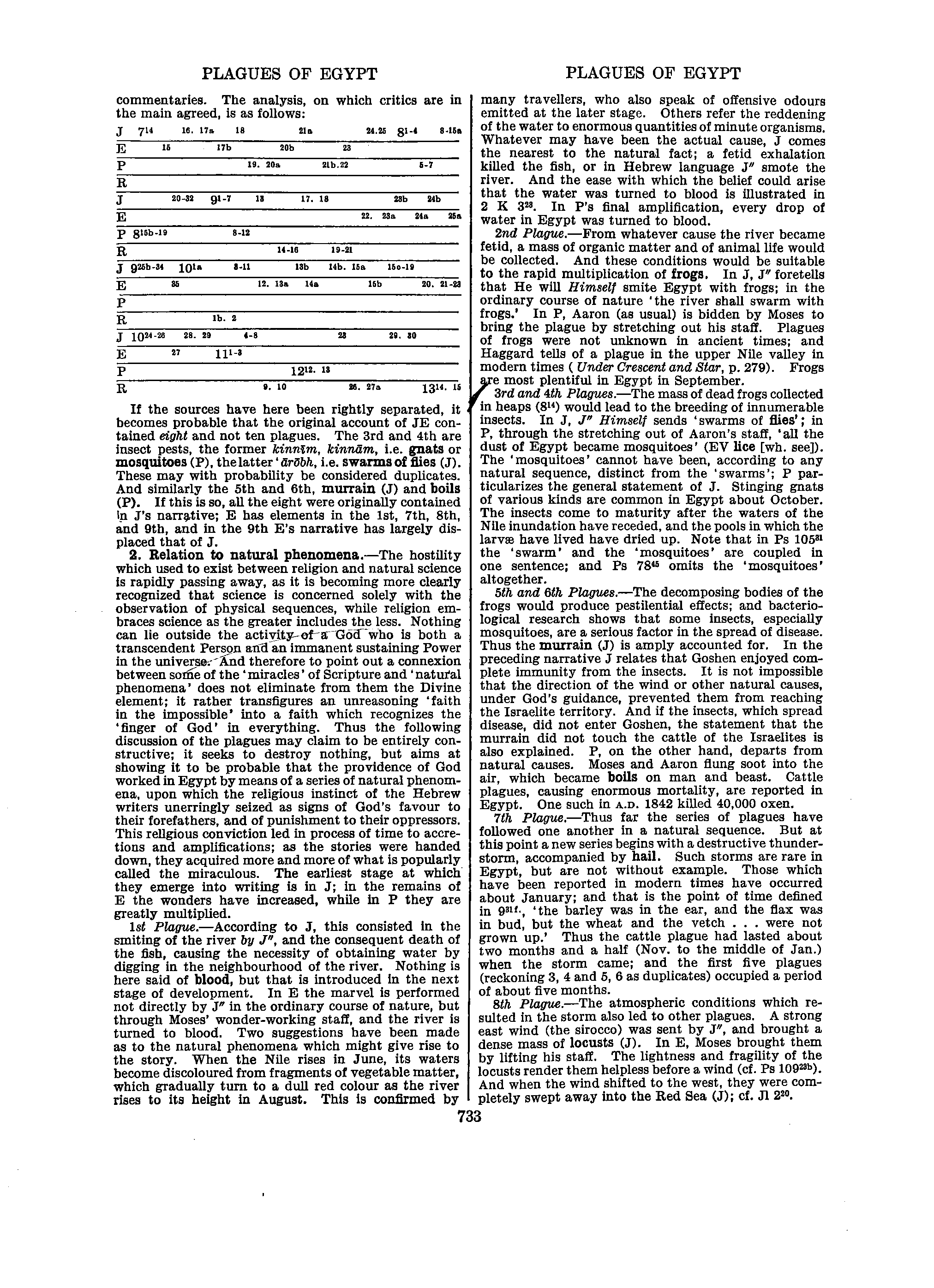

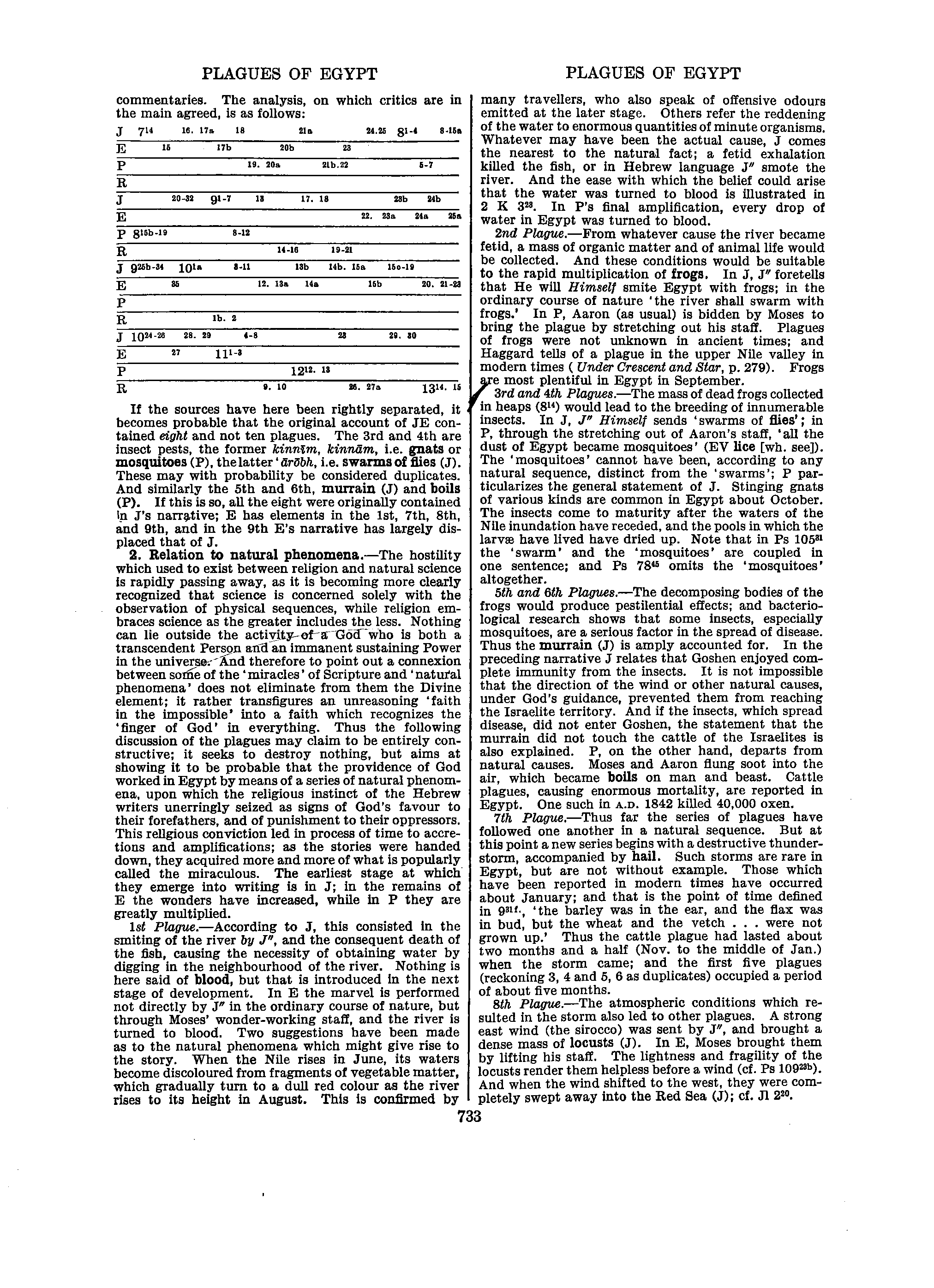

commentaries.

The

analysis,

on

which

critics

are

in

the

main

agreed,

is

as

follows:

If

the

sources

have

here

been

rightly

separated,

becomes

probable

that

the

original

account

of

JE

con-tained

eight

and

not

ten

plagues.

The

3rd

and

4th

are

insect

pests,

the

former

kinnlm,

kinnam,

i.e.

gnats

or

mosquitoes

(P),

the

latter

'SrSb/i,

i.e.

swarms

of

flies

(J).

These

may

with

probability

be

considered

duplicates.

And

similarly

the

5th

and

6th,

murrain

(J)

and

boils

(P).

It

this

is

so,

all

the

eight

were

originally

contained

In

J's

narrative;

E

has

elements

in

the

1st,

7th,

8th,

and

9th,

and

m

the

9th

E's

narrative

has

largely

dis-placed

that

of

J.

2.

Relation

to

natural

phenomena.

—

The

hostility

which

used

to

exist

between

religion

and

natural

science

is

rapidly

passing

away,

as

it

is

becoming

more

clearly

recognized

that

science

is

concerned

solely

with

the

observation

of

physical

sequences,

while

religion

em-braces

science

as

the

greater

includes

the

less.

Nothing

can

lie

outside

the

activity-of-a

God^

who

is

both

a

transcendent

Person

anU

an

immanent

sustaining

Power

in

the

univers&.'^nd

therefore

to

point

out

a

connexion

between

some

of

the

'

miracles

'

of

Scripture

and

'

natm'al

phenomena'

does

not

eliminate

from

them

the

Divine

element;

it

rather

transfigures

an

unreasoning

'faith

in

the

impossible'

into

a

faith

which

recognizes

the

'finger

of

God'

in

everything.

Thus

the

following

discussion

of

the

plagues

may

claim

to

be

entirely

con-structive;

it

seelss

to

destroy

nothing,

but

aims

at

showing

it

to

be

probable

that

the

providence

of

God

worked

in

Egypt

by

means

of

a

series

of

natural

phenom-ena,

upon

which

the

religious

instinct

of

the

Hebrew

writers

unerringly

seized

as

signs

of

God's

favour

to

their

forefathers,

and

of

punishment

to

their

oppressors.

This

religious

conviction

led

m

process

of

time

to

accre-tions

and

amplifications;

as

the

stories

were

handed

down,

they

acquired

more

and

more

of

what

is

popularly

called

the

miraculous.

The

earliest

stage

at

which

they

emerge

into

writing

is

in

J;

in

the

remains

of

E

the

wonders

have

increased,

while

in

P

they

are

greatly

multiplied.

1st

Plague.

—

According

to

J,

this

consisted

in

the

smiting

of

the

river

by

J",

and

the

consequent

death

of

the

fish,

causing

the

necessity

of

obtaining

water

by

digging

in

the

neighbourhood

of

the

river.

Nothing

is

here

said

of

blood,

but

that

is

introduced

in

the

next

stage

of

development.

In

E

the

marvel

is

performed

not

directly

by

J"

in

the

ordinary

course

of

nature,

but

through

Moses'

wonder-working

staff,

and

the

river

is

turned

to

blood.

Two

suggestions

have

been

made

as

to

the

natural

phenomena

which

might

give

rise

to

the

story.

When

the

Nile

rises

in

June,

its

waters

become

discoloured

from

fragments

of

vegetable

matter,

which

gradually

turn

to

a

dull

red

colour

as

the

river

rises

to

its

height

in

August.

This

is

confirmed

by

733

PLAGUES

OF

EGYPT

many

travellers,

who

also

speak

of

offensive

odours

emitted

at

the

later

stage.

Others

refer

the

reddening

of

the

water

to

enormous

quantities

of

minute

organisms.

Whatever

may

have

been

the

actual

cause,

J

comes

the

nearest

to

the

natural

fact;

a

fetid

exhalation

killed

the

fish,

or

in

Hebrew

language

J"

smote

the

river.

And

the

ease

with

which

the

belief

could

arise

that

the

water

was

turned

to

blood

is

illustrated

in

2

K

3^.

In

P's

final

amplification,

every

drop

of

water

in

Egypt

was

turned

to

blood.

2nd

Plague.

—

From

whatever

cause

the

river

became

fetid,

a

mass

of

organic

matter

and

of

animal

life

would

be

collected.

And

these

conditions

would

be

suitable

to

the

rapid

multiplication

of

frogs.

In

J,

J"

foretells

that

He

will

Himselt

smite

Egypt

with

frogs;

in

the

ordinary

course

of

nature

'the

river

shall

swarm

with

frogs.'

In

P,

Aaron

(as

usual)

is

bidden

by

Moses

to

bring

the

plague

by

stretching

out

his

staff.

Plagues

of

frogs

were

not

unknown

in

ancient

times;

and

Haggard

tells

of

a

plague

in

the

upper

Nile

valley

in

modern

times

(

Under

Crescent

and

Star,

p.

279).

Frogs

^^

are

most

plentiful

in

Egypt

in

September.

1*

■

y^

3rd

and

ith

Plagues.

—

The

mass

of

dead

frogs

collected

it

,

'

in

heaps

(8")

would

lead

to

the

breeding

of

innumerable

insects.

In

J,

J"

Himself

sends

'swarms

of

flies';

in

P,

through

the

stretching

out

of

Aaron's

staff,

'all

the

dust

of

Egypt

became

mosquitoes'

(EV

lice

[wh.

see]).

The

'mosquitoes'

cannot

have

been,

according

to

any

natural

sequence,

distinct

from

the

'swarms';

P

par-ticularizes

the

general

statement

of

J.

Stinging

gnats

of

various

kinds

are

common

in

Egypt

about

October.

The

insects

come

to

maturity

after

the

waters

of

the

Nile

inundation

have

receded,

and

the

pools

in

which

the

larvae

have

lived

have

dried

up.

Note

that

in

Ps

105"

the

'swarm'

and

the

'mosquitoes'

are

coupled

in

one

sentence;

and

Ps

78"

omits

the

'mosquitoes'

altogether.

5th

and

6th

Plagues.

—

The

decomposing

bodies

of

the

frogs

would

produce

pestilential

effects;

and

bacterio-logical

research

shows

that

some

insects,

especially

mosquitoes,

are

a

serious

factor

in

the

spread

of

disease.

Thus

the

murrain

(J)

is

amply

accounted

for.

In

the

preceding

narrative

J

relates

that

Goshen

enjoyed

com-plete

immunity

from

the

insects.

It

is

not

impossible

that

the

direction

of

the

wind

or

other

natural

causes,

under

God's

guidance,

prevented

them

from

reaching

the

Israelite

territory.

And

if

the

insects,

which

spread

disease,

did

not

enter

Goshen,

the

statement

that

the

murrain

did

not

touch

the

cattle

of

the

Israelites

is

also

explained.

P,

on

the

other

hand,

departs

from

natural

causes.

Moses

and

Aaron

fiung

soot

into

the

air,

which

became

boils

on

man

and

beast.

Cattle

plagues,

causing

enormous

mortality,

are

reported

in

Egypt.

One

such

in

a.d.

1842

killed

40,000

oxen.

7th

Plague.

—

Thus

far

the

series

of

plagues

have

followed

one

another

in

a

natural

sequence.

But

at

this

point

a

new

series

begins

with

a

destructive

thunder-storm,

accompanied

by

hail.

Such

storms

are

rare

in

Egypt,

but

are

not

without

example.

Those

which

have

been

reported

in

modern

times

have

occurred

about

January;

and

that

is

the

point

of

time

defined

in

93H._

'the

barley

was

in

the

ear,

and

the

fiax

was

in

bud,

but

the

wheat

and

the

vetch

.

.

.

were

not

grown

up.'

Thus

the

cattle

plague

had

lasted

about

two

months

and

a

half

(Nov.

to

the

middle

of

Jan.)

when

the

storm

came;

and

the

first

five

plagues

(reckoning

3,

4

and

6,

6

as

duplicates)

occupied

a

period

of

about

five

months.

8th

Plague.

—

The

atmospheric

conditions

which

re-sulted

in

the

storm

also

led

to

other

plagues.

A

strong

east

wind

(the

sirocco)

was

sent

by

J",

and

brought

a

dense

mass

of

locusts

(J).

In

E,

Moses

brought

them

by

lifting

his

staff.

The

lightness

and

fragility

of

the

locusts

render

them

helpless

before

a

wind

(cf.

Ps

lOQ^s'').

And

when

the

wind

shifted

to

the

west,

they

were

com-pletely

swept

away

into

the

Red

Sea

(J);

cf.

Jl

2".