TEMPLE

The

real

depth

was

doubtless,

as

in

Solomon's

Temple

(5'3),

10

cubits

in

the

centre,

but

now

increased

to

20

cubits

at

the

wings

(so

Josephus).

As

the

plan

shows,

the

porch

outflanlced

the

main

body

of

the

Temple,

which

was

60

—

the

Mishna

has

70

—

cubits

in

breadth,

by

18

cubits

at

either

wing.

These

dimensions

show

that

Herod's

porch

resembled

the

pylons

of

an

Egyptian

temple.

It

probably

tapered

towards

the

top,

and

was

surmounted

by

an

Egyptian

cornice

with

thefamiliareavettomouIding(cf.

sketch

below).

The

entrance

to

the

porch

measured

40

cubits

by

20

{Mlddoth,

iii.

7),

corresponding

to

the

dimensions

of

'the

holy

place.'

There

was

no

door.

The

'great

door

of

the

house'

(20

cubits

by

10)

was

'all

over

covered

with

gold,'

in

front

of

which

hung

a

richly

embroidered

Babylonian

veil,

while

above

the

lintel

was

figured

a

huge

golden

vine

(Jos.

Ant.

xv.

xi.

3,

BJ

v.

V.

4).

The

Interior

area

of

Herod's

Temple

was,

for

obvious

reasons,

the

same

as

that

of

its

predecessors.

A

hall,

61

cubits

long

by

20

wide,

was

divided

between

the

holy

place

(40

by

20,

but

with

the

height

increased

to

40

cubits

[Middoth,

iv.

6])

and

the

most

holy

place

(20

by

20

by

20

high).

The

extra

cubit

was

occupied

by

a

double

curtain

embroidered

in

colours,

which

screened

off

'the

holy

of

holies'

(et.

Midd.

iv.

7

with

YBmS,

v.2).

This

is

the

veil

o£

the

Temple

referred

to

in

Mt

27"

and

||

(cf.

He

6'3

etc.).

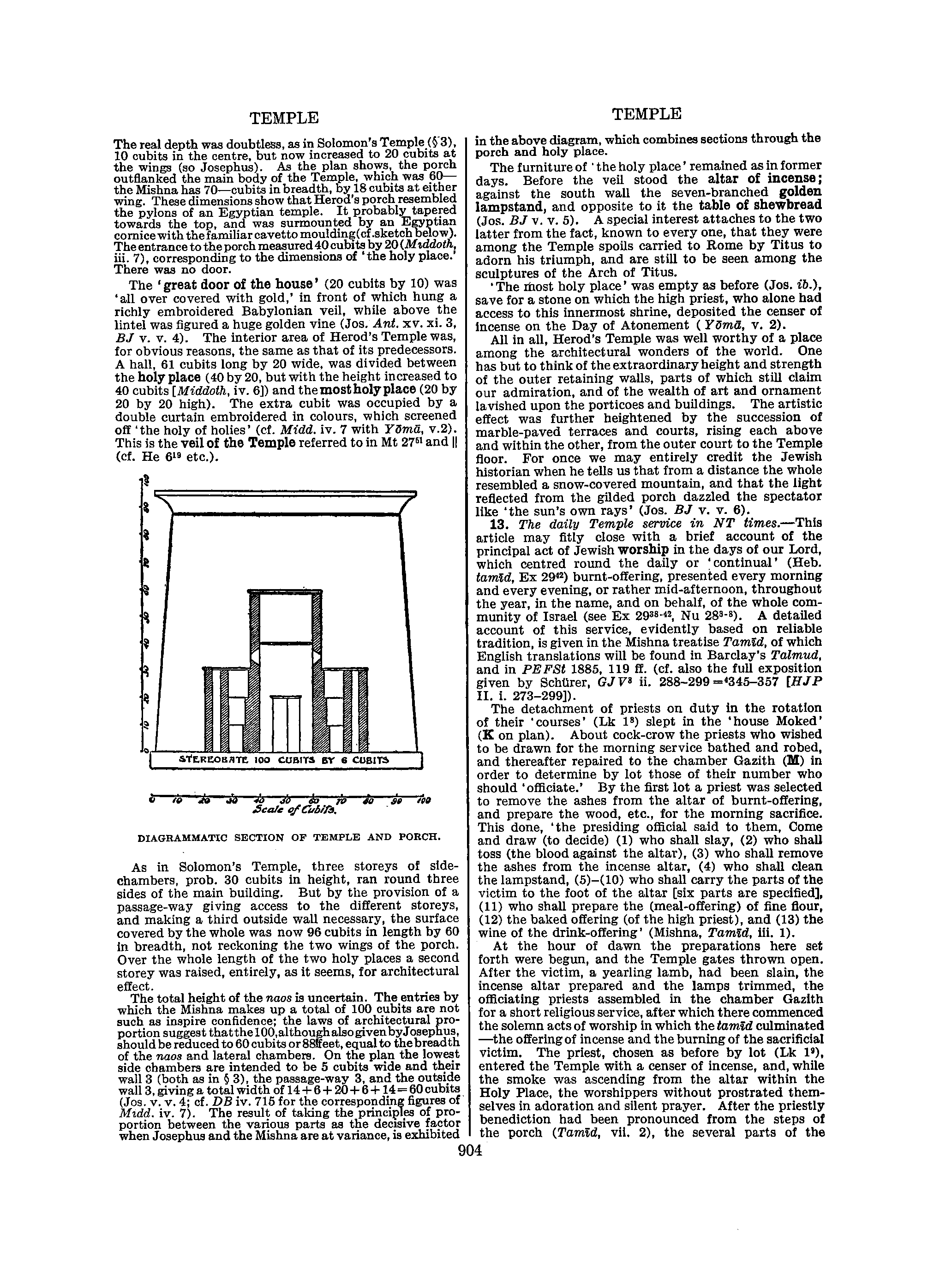

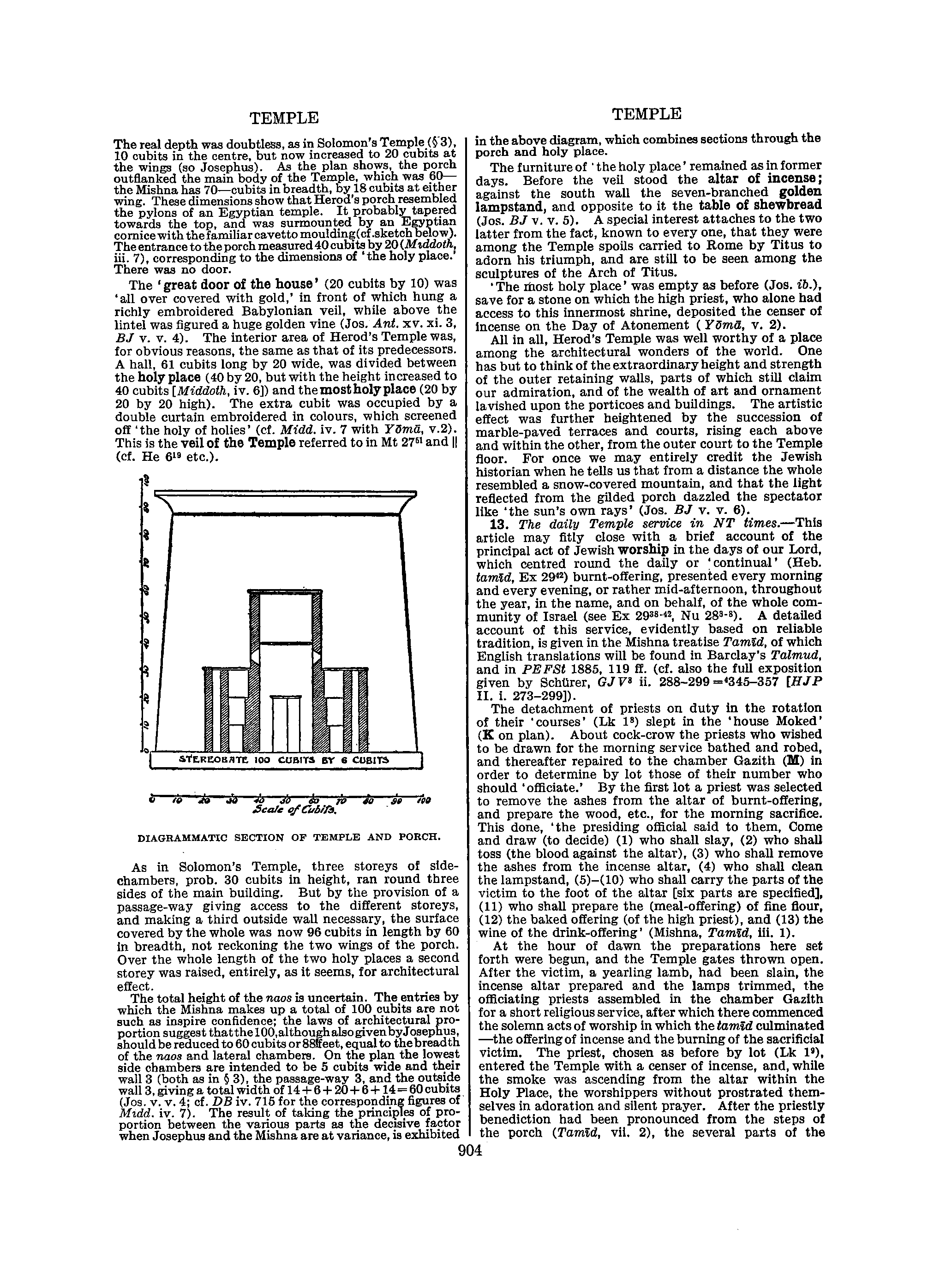

DIAGRAMMATIC

SECTION

OF

TEMPLE

AND

PORCH.

As

in

Solomon's

Temple,

three

storeys

of

side-chambers,

prob.

30

cubits

in

height,

ran

round

three

sides

of

the

main

building.

But

by

the

provision

of

a

passage-way

giving

access

to

the

different

storeys,

and

making

a

third

outside

wall

necessary,

the

surface

covered

by

the

whole

was

now

96

cubits

in

length

by

60

in

breadth,

not

reckonuig

the

two

wings

of

the

porch.

Over

the

whole

length

of

the

two

holy

places

a

second

storey

was

raised,

entirely,

as

it

seems,

for

architectural

effect.

The

total

height

of

the

naos

is

uncertain.

Theentries

by

which

the

Mishna

makes

up

a

total

of

100

cubits

are

not

such

as

inspire

confidence;

the

laws

of

architectural

pro-portion

suggest

thatthelOO,although

also

given

byjosephus,

should

be

reduced

to

60

cubits

or

SSBeet,

equal

to

the

breadth

of

the

tiojos

and

lateral

chambers.

On

the

plan

the

lowest

side

chambers

are

intended

to

be

5

cubits

wide

and

their

wall

3

(both

as

in

§

3),

the

passage-way

3,

and

the

outside

wall

3,

giving

a

total

width

of

14

-I-

6

-I-

20

-I-

6

-H4=

60

cubits

(Jos.

v.

V.

4;

cf

.

DB

iv.

715

for

the

corresponding

figures

of

Midd.

iv.

7).

The

result

of

taking

the

principles

of

pro-portion

between

the

various

parts

as

the

decisive

factor

when

Josephus

and

the

Mishna

are

at

variance,

is

exhibited

TEMPLE

in

the

above

diagram,

which

combines

sections

through

the

porch

and

holy

place.

The

furniture

of

'

the

holy

place

'

remained

as

in

former

days.

Before

the

veil

stood

the

altar

of

incense;

against

the

south

wall

the

seven-branched

golden

lampstand,

and

opposite

to

it

the

table

of

shewbread

(Jos.

BJ

V.

V.

5).

A

special

interest

attaches

to

the

two

latter

from

the

fact,

known

to

every

one,

that

they

were

among

the

Temple

spoils

carried

to

Rome

by

Titus

to

adorn

his

triumph,

and

are

still

to

be

seen

among

the

sculptures

of

the

Arch

of

Titus.

'

The

itiost

holy

place

'

was

empty

as

before

(Jos.

ib.),

save

for

a

stone

on

which

the

high

priest,

who

alone

had

access

to

this

innermost

shrine,

deposited

the

censer

of

Incense

on

the

Day

of

Atonement

(

YBmS,

v.

2).

All

in

all,

Herod's

Temple

was

well

worthy

of

a

place

among

the

architectural

wonders

of

the

world.

One

has

but

to

think

of

the

extraordinary

height

and

strength

of

the

outer

retaining

walls,

parts

of

which

still

claim

our

admiration,

and

of

the

wealth

of

art

and

ornament

lavished

upon

the

porticoes

and

buildings.

The

artistic

effect

was

further

heightened

by

the

succession

of

marble-paved

terraces

and

courts,

rising

each

above

and

within

the

other,

from

the

outer

court

to

the

Temple

floor.

For

once

we

may

entirely

credit

the

Jewish

historian

when

he

tells

us

that

from

a

distance

the

whole

resembled

a

snow-covered

mountain,

and

that

the

light

reflected

from

the

gilded

porch

dazzled

the

spectator

like

'the

sun's

own

rays'

(Jos.

BJ

v.

v.

6).

13.

The

daily

Temple

service

in

NT

times.

—

This

article

may

fitly

close

with

a

brief

account

of

the

principal

act

of

Jewish

worship

in

the

days

of

our

Lord,

which

centred

round

the

daily

or

'continual'

(Heb.

iamld.

Ex

29«)

burnt-offering,

presented

every

morning

and

every

evening,

or

rather

mid-afternoon,

throughout

the

year,

in

the

name,

and

on

behalf,

of

the

whole

com-munity

of

Israel

(see

Ex

2938-«,

Nu

28'-»).

A

detailed

account

of

this

service,

evidently

based

on

reliable

tradition,

is

given

in

the

Mishna

treatise

Tamtd,

of

which

English

translations

will

be

found

in

Barclay's

Talmud,

and

in

PEFSt

1885,

119

ff.

(cf.

also

the

full

exposition

given

by

SchUrer,

GJV>

ii.

288-299

='345-357

IHJP

II.

i.

273-299]).

The

detachment

of

priests

on

duty

In

the

rotation

of

their

'courses'

(Lk

1')

slept

in

the

'house

Moked'

(K

on

plan).

About

cock-crow

the

priests

who

wished

to

be

drawn

for

the

morning

service

bathed

and

robed,

and

thereafter

repaired

to

the

chamber

Gazith

(M)

in

order

to

determine

by

lot

those

of

their

number

who

should

'officiate.'

By

the

first

lot

a

priest

was

selected

to

remove

the

ashes

from

the

altar

of

burnt-oflering,

and

prepare

the

wood,

etc.,

for

the

morning

sacrifice.

This

done,

'the

presiding

official

said

to

them.

Come

and

draw

(to

decide)

(1)

who

shall

slay,

(2)

who

shall

toss

(the

blood

against

the

altar),

(3)

who

shall

remove

the

ashes

from

the

incense

altar,

(4)

who

shall

clean

the

lampstand,

(5)-(10)

who

shall

carry

the

parts

of

the

victim

to

the

foot

of

the

altar

[six

parts

are

specified],

(11)

who

shall

prepare

the

(meal-offering)

of

fine

flour,

(12)

the

baked

offering

(of

the

high

priest),

and

(13)

the

wine

of

the

drink-offering'

(Mishna,

Tamld,

iii.

1).

At

the

hour

of

dawn

the

preparations

here

set

forth

were

begun,

and

the

Temple

gates

thrown

open.

After

the

victim,

a

yearling

lamb,

had

been

slain,

the

incense

altar

prepared

and

the

lamps

trimmed,

the

officiating

priests

assembled

in

the

chamber

Gazith

for

a

short

religious

service,

after

which

there

commenced

the

solemn

acts

of

worship

in

which

the

tamid

culminated

—

the

offering

of

incense

and

the

burning

of

the

sacrificial

victim.

The

priest,

chosen

as

before

by

lot

(Lk

1'),

entered

the

Temple

with

a

censer

of

incense,

and,

while

the

smoke

was

ascending

from

the

altar

within

the

Holy

Place,

the

worshippers

without

prostrated

them-selves

in

adoration

and

silent

prayer.

After

the

priestly

benediction

had

been

pronounced

from

the

steps

of

the

porch

(.Tamld,

vii.

2),

the

several

parts

of

the